by Gregory Moomjy

Death in opera is so ubiquitous, it’s cliché. But it wasn’t always like that. Prior to the French Revolution, the majority of Italian opera glorified a world in which the ruler was the center. And although they occasionally struggled for the good of the state, there was always a happy ending and the Crown, even if it changed hands, was always safe. But, the French Revolution showed us that monarchs are fallible and a happy ending is not always assured, even for royalty. When faced with the social changes brought on by revolutionary France, opera had to adapt. In order for any art form to last 400 years like opera has, it has to be malleable and able to adjust to a variety of kings, popes, wars and revolutions.

Consequently, the dying lead was born as opera’s way of adapting to the social changes brought on by the French Revolution.

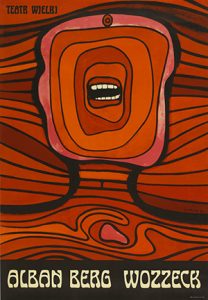

In much the same way, World War I changed the direction opera would take for the rest of the 20th century. This is most evident in Alban Berg’s masterpiece Wozzeck which premiered in 1925. Berg first became acquainted with the source material before the war, which delayed its completion. The war also exerted immense influence on the libretto and the music. When the opera returns to the Met this December in a new production by South African director William Kentridge, “the war to end all wars” is front and center.

The opera’s source material is a play of the same name by Georg Büchner. The play, originally titled Woyzeck, is about Johann Christian Woyzeck, a German soldier in 1821 who was convicted of the murder of a woman he was living with. He was executed, despite proof of insanity from a doctor. Insanity is a driving force behind the many iterations of the play including Berg’s opera. Over an incredibly compact and powerful 90 minutes we meet a low-ranking soldier who is not only mentally unstable but gets beat up by his superiors, abused by a quack who performs bogus medical experiments and goes home to his estranged relationship and his son.

The opera’s source material is a play of the same name by Georg Büchner. The play, originally titled Woyzeck, is about Johann Christian Woyzeck, a German soldier in 1821 who was convicted of the murder of a woman he was living with. He was executed, despite proof of insanity from a doctor. Insanity is a driving force behind the many iterations of the play including Berg’s opera. Over an incredibly compact and powerful 90 minutes we meet a low-ranking soldier who is not only mentally unstable but gets beat up by his superiors, abused by a quack who performs bogus medical experiments and goes home to his estranged relationship and his son.

At first glance, this looks similar to the slice of life operas of Puccini, Mascagni and Leoncavallo which came out of Italy at the turn of the twentieth century. However, Wozzeck takes Italy’s Verismo School to the next step. In an opera like Madama Butterfly, Puccini still wrote lyrical diatonic arias with plush orchestration. Wozzeck is an atonal masterpiece. Atonality is simply music composed in a way that ignores the natural pull towards resolution that the human ear craves. A good example of this would be Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde, a four-hour opera in which the audience is denied resolution until the last ten minutes of the piece. In Wagner’s meta musical philosophy, he pushes the bounds of tonality in order to show that as long as Tristan and Isolde remain alive, they cannot be together.

Therefore, it is only when they die that they can finally be at peace and the opera ends in bright D major. However, what Wagner began in Tristan would become the Expressionist School headed by composers like Arnold Schoenberg, Alban Berg and Anton Webern, also known as the Second Viennese School in homage to Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven, who formed the First Viennese School. These composers ignored the commonplace rules of tonality—some of them even argued that they “liberated” music from tonality, in order to plumb the depths of the psyche.

Expressionism and by consequence, atonality, became the ideal musical language for composers who tried to make sense of the chaos wrought by WWI and its aftermath.

In Wozzeck, Berg creates a sort of hybrid musical language. He applies atonality to more classical forms that are tied to the action in each scene. For instance, the music in the scene with Marie and her child is based off a lullaby and the tavern scenes are populated with polkas on an out-of-tune piano. The combination of atonality and established musical forms can lead to moments of great beauty, such as in the orchestral interlude that accompanies Wozzeck’s return to the lake to destroy the evidence of the murder.

WWI also exerts its influence on the libretto. Berg wrote his own text which included details from his brief service in the Austro-Hungarian army. Thankfully, Berg was transferred to a desk job where he finished his service. Still, comments about rations, probably based on his own remarks in letters home, made it into the libretto along with a ‘snoring chorus’ in the barracks.

The new production which premieres December 27 will be directed by William Kentridge and is the first new production of Wozzeck at the Met in 20 years. Although his work has been seen at the Met on various occasions, Wozzeck is a particularly important piece since Kentridge also directed a recent new production of Berg’s Grand Opera, Lulu. According to Kentridge, the central element of this production will be a grainy, gray overcast background onto which he will project images of bombs, planes, explosions associated not only with WWI but also with the grotesque images that are spinning around Wozzeck’s mind. Although there is no specific time period in which the opera takes place, Kentridge sees his production as a premonition of WWI.

This is why Wozzeck is so powerful. The opera, a masterpiece of atonality, uses the perfect musical language to illustrate the chaos and mass devastation wrought by the Great War. Modern audiences know what will happen. Not only do they know about the chaos and carnage, but they know about the long-ranging consequences of WWI which some historians argue lasted until the Vietnam War. Musically whether atonality, and the prevalence it gained in 20th century music, is harmful is a separate question. However, it must be agreed that when artists are faced with such widespread devastation, they need to have the appropriate language with which to explore it. In Wozzeck, Berg shows a powerful way to come to terms with such unforeseen bloodshed.

Wozzeck is running at the Metropolitan Opera December 27, 2019 through January 22, 2020.

Photo: Ruth Walz / Salzburg Festival

He must have meant Haydn (Hayden???). The meaning of several sentences that do not conform to English grammar as we know it, can be similarly guessed.

Hey Andre! Amazed that you read our website. I fixed Haydn. Certainly appreciate any feedback you can give. -Peter comments@indieopera.com